In the autumn of 2006, I had a lovely visit to the Avignon area in the south of France. One day, the group I was with went to the bustling, open-air, Friday market in Carpentras. There I came upon a man sitting alone in front of a little table. He was selling something I had never seen before. It looked like a short dowel of wood with a metal strip wrapped around the smaller end. I had been looking for a souvenir top commemorate my first time in France, so I took a look at these peculiar things. It wasn’t long before I learned that this idiosyncratic, little contraption was actually a pocketknife. The entirety of my experience with pocketknives up to that point had been with a small, old 1974 Case XX 6227 Small Jack and a mid-1970s model of a Buck 110 that were in my father’s collection. In other words, I knew nothing, and wasn’t really interested in the world of knives (not yet!). I was told by the man at the table that it was a French pocketknife called Opinel. I opened and closed it a few times (it was definitely a 2-handed knife), looked it over, then put it down, thanked him for this time, and moved on. I may have known nothing about pocketknives, but I knew that what I looked at had no appeal to me.

It’s been quite a while now, and I have since become very interested in the world of pocketknives, starting with blade steel metallurgy. Over that time, I have heard so much disparagement toward Opinel knives that I, despite my mere 30-second introduction to the brand and their products so long ago, I related to the criticisms of it being an antiquated design, an odd little product that used a cheap wooden dowel handle and a soft, rust-prone blade. But I also like to challenge my assumptions, especially when I recognize they are based on so little factual information, so I picked up an Opinel No. 9 Carbone on sale over the December holidays to really see what I thought.

This post is my review of that Opinel knife. Let’s get into it.

TL;DR

There is a tall tale that says “opinel” means “folding knife” in French. However, the company founder, Joseph Opinel, named the company after himself. So does that mean some Gallic dude in France in 1890, who’s literally named “Joe Folding Knife”, started his own folding knife company in 1890? How ironic is that, assuming it’s true? Let’s say I have my doubts.

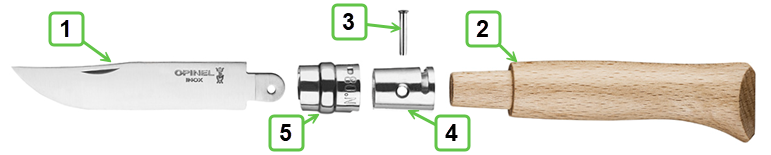

Regardless, the original Opinel is a knife of the ancients. Joseph Opinel’s (who would really benefit from a significant upgrade in modern hipness, so from now on, I’m referring to him as JoeOp) knife design was very simple. The original model consisted of only 4 parts:

- Blade

- Handle Haft

- Pivot Axle

- Metal collar ferrule on the top end of haft

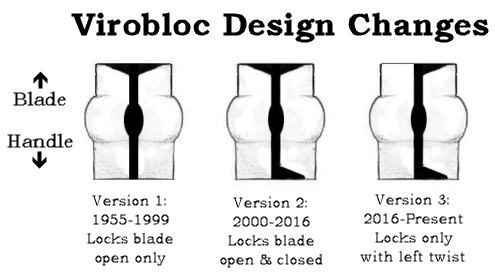

In 1955, the design incrementally changed when a new, 5th part was added. The Virobloc, the twisting safety lock ring, was installed on top of the metal collar ferrule. Lastly, in 1986, a second blade steel option appeared with the arrival of Sandvik 12C27 stainless steel, with a claimed 55-57 HRc, which Opinel dubbed “Inox”, short for the French word, inoxydable, meaning stainless.

The simplicity of the Opinel design made it easy to build and sell. It became a very popular tool with farmers and tradespeople, and with consistent, thoughtful marketing, the Opinel family cutlery business took off!

Opinel is proud to say that their knife design hasn’t changed in 135 years. That fact is true, but I’m not so sure that it should be a point of pride. The design is outdated, the functionality is antiquated, and the materials are what was considered good, well, 135 years ago, but not so much today. Time has progressed, but it seems Opinel has not.

To be fair, if we look beyond the original numbered series of pocketknives, we see that Opinel has been working to expand their product lines. They now create kitchenware, tableware, gardening and landscape cutting tools, new multi-tools, all manner of culinary cutlery, and of course, a greatly expanded array of folding pocketknives, at least new in terms of haft (“haft” is the term Opinel uses for what we call the handle) colors, applied designs, and in a few, specialized cases, new FRN-type hafts.

But Opinel is still hampered by continuing to only offer blades in either ancient, soft, highly rust-prone, high-carbon steel or their out-of-date, ultra-budget line of “Martensitic stainless steel” (Sandvik 12C27), also a very soft steel by today’s standards. These are disappointing products in today’s world of advanced metallurgical, blade steel products. Heck, even the old traditional, American knife brands, Buck and Case, are now making new knives with modern, super-premium steels and handles, made of the newest materials available, no longer reliant on pinned handle construction, but instead use screw fasteners for removable scales, include pocket clips, and employ modern folding knife locks and deployment mechanisms. You can even buy modern takes on slip-joint Barlow knives that wield carbon fiber handles and particle metallurgy blades!

It’s easy to conclude that life at Opinel seems to have largely passed them by. I’d urge our friends at Opinel to stop for a moment and peer out the window! There’s a whole new world to behold in the pocketknife industry! New blade materials, new handle materials, new finishes, new ways to mount and support a blade to the handle, and new ways to open a knife, all of that being significant upgrades to the current Opinel knives! Please! Wake up, smell the expresso (that IS the correct term in French for Italian espresso), and dream a little dream! C’mon, homme!

Pros

- It’s cheap!

- The blade comes very sharp out of its zip-top baggie packaging.

- It comes with a single-sided nail nick to help you open the blade – at no additional charge!

- It has a contoured, integral handle.

- There is a blade lock.

- If you’re ever lost in the backwoods, you can burn that wooden handle for 3 whole minutes of comforting heat. And who knows? You might increase the blade’s HRc level at the same time!

- The company logo looks like a finger gun hand shooting a mock double-barrel derringer at a royal crown. Was the company founder related to Gavrilo Princip?

Cons

- The basic design of the knife hasn’t changed for over 135 years! Hey, fellas! Did you forget to do something? Yeah.

- The official knife packaging, at least what I received from KnifeCenter, was a zip-top baggie. Very Impressive!

- The “integral” handle is a wooden dowel.

- The XC90 “Carbone” steel has terrible edge retention and dulls very quickly. Very quickly.

- The steel also has even worse corrosion (rust) resistance. You can practically watch it become rusty.

- When rust gets down into the haft slot pivot, unless you want to attempt to disassemble it, your knife is now on terminal life support.

- It’s a 2-handed opening knife only.

- The blade lock is also 2-handed.

- It’s 2-handed for closing as well.

- The pivot “action”, if you call it that, is almost non-actionable. That’s why Opinel calls their washerless/bearingless pivot in this knife (wood-on-steel) an “axle”.

- The harsh, non-beveled 90° blade spine edge is what is universally known as “Spyderco sharp”.

Tech Specs

Brand | Opinel |

Website | |

Manufacturer | Opinel |

Origin | Chambéry, Savoy, France |

Model Reviewed | Opinel No. 9 |

Designer/Design | Joseph Opinel |

Model Launch Year | 1897 |

Style | Folding knife |

Lock Type | Virobloc (aka safety twist lock or locking ring) |

Opening Type | 2-handed manual |

Opening Mechanism(s) | Nail nick |

Pivot Type | Riveted stainless steel pin (axle) |

Pivot Mechanism | steel axle |

Length Closed | 118.22 mm (4.655") |

Length Opened | 207.44 mm (8.167") |

Weight | 54.72 g (1.93 oz.) |

Weight-to-Blade-Length Ratio | 0.61 |

Original Packaging | A small, zip-top baggie (from KnifeCenter) |

Edge | Plain |

Shape | Yatagan (a long clip point blade slightly angled downward from the handle centerline) |

Material | XC90 Carbone high carbon steel |

Claimed Hardness HRc | 57-59 |

Blade Length | 90.02 mm (3.54") |

Cutting Edge Length | 90.02 mm (3.54") |

Primary Bevel Angle | 2° |

Original Edge Angle | 6° (Opinel claims 20° -- 10° per side, but my laser goniometer disagreed) |

Height | 18.74 mm (0.738") |

Thickness | 1.79 mm (0.072") |

Main Bevel Edge Thickness | 0.23 mm (0.0085") |

Finish | Satin |

Features | Crazy thin |

Grind | Full-flat grind with convex edge |

Swedge | None |

Fuller | None |

Jimping | None |

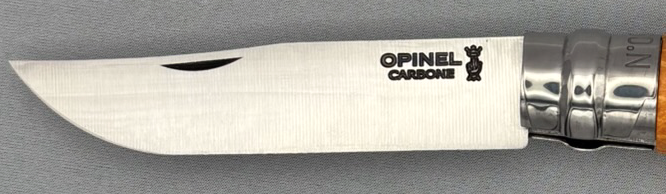

Blade Markings | Show (left) side: Top line: Deeply stamped company name; 2nd line: stamped steel model name. To the right is the stamped company logo, positioned under the spine, very close to the top of handle |

Sharpening Choil | None |

On-Blade Opening Assists | Nail nick |

Materials | Cylindrical varnished Beechwood |

Color | Cappuccino |

Scale Texture | Smooth |

Handle/Scale Features | Contoured, rounded wooden handle with stainless steel twisting locking ring at top of handle, sculpted "fishtail" at back |

Liners | None |

Opening Stop Pin Type | None |

Handle Length | 118.22 mm (4.655") |

Blade-to-Handle Ratio | 0.76 |

Closed Handle Height | 24.56 mm (0.967") |

Handle Thickness | 22.03 mm (0.868") |

Pivot Center-to-Open-Knife Fulcrum | 6.98 mm (0.275") |

Integral Handle | Sort of, yes |

Backspacing Type | None |

Tang Features | No washers or bearings! |

Lanyard Mount | None |

Pocket Clip | None |

Fasteners | None |

History of Opinel

Opinel is a very old brand. How old? Well, legend tells of it going back into ancient, even archaic times, as I understand it. My research revealed that way back in distant time, back when Neanderthals still roamed the plains of Europe, apparently one Neander-dude invented a folding pocketknife. At least, this story is as likely as any other history told about Opinel. Given its antiquated design, I did some online research about its origins (online research is the BEST!), and I believe this documented conversation between the Neander-dude inventor and his Tall friend explains it all:

Smuh: Me invent thing.

Gloo: What you invent, Smuh?

Smuh: I invent blade.

Gloo: What blade made of?

Smuh: I invent metal to make blade.

Gloo: How you make metal?

Smuh: I burn much red dirt with hot fire in ash of burnt log.

Gloo: What blade do?

Smuh: Blade cut stuff.

Gloo: We have obsidian cutters. Is blade sharper than obsidian?

Smuh: No.

Gloo: Then why invent blade of metal?

Smuh: It better than obsidian.

Gloo: How? You say not as sharp.

Smuh: Yes, but less brittle. Won’t break or chip as fast.

Gloo: Ah! This is bad problem with obsidian. Show me blade.

Smuh: (Smuh hands Gloo a short, thin, narrow blade with only a small rounded tang.) What you think?

Gloo: It is already rusty! Hmmm. How to hold blade? Not sharp end too short!

Smuh: I not invent that yet.

Gloo: Invent blade holder. Call it handle.

Smuh: Yes. I invent handle!

Gloo: How you put blade away?

Smuh: What you mean, Gloo?

Gloo: Store blade when not using. Make slot in handle, fold blade in handle.

Smuh: Yes. I invent handle with slot to store folded blade!

Gloo: What handle made of?

Smuh: Don’t know yet. Reindeer bone?

Gloo: Too messy, not good enough.

Smuh: Antler?

Gloo: Too hard. Obsidian break before cut done. Maybe use stick on ground. Stick cheap and easy to find.

Smuh: I invent handle of stick with slot to fold blade!

Gloo: How to keep blade open when using?

Smuh: You mean lock?

Gloo: Yes. Blade need lock.

Smuh: What kind lock?

Gloo: Maybe use thinner blade metal, wrap around end of stick, make twist metal to block blade fold on fingers

Smuh: I invent lock made of thin metal wrapped around end of stick! I twist metal to lock.

Gloo: What you name lock?

Smuh: I call it … Lock!

Gloo: Not good. Need better lock name to ring bell.

Smuh: I invent Ring Lock!

Gloo: No. You not lock ring. Use ring to lock blade.

Smuh: I invent Lock Ring!

Gloo: How many you make?

Smuh: 13, each one bigger.

Gloo: What is brand name of new blade and handle invention?

Smuh: Don’t know yet.

Gloo: OK. I go home now to cave in Opinel. Good luck with name.

Smuh: Hmmm.

It turns out that this story may not be the “exact” origin history of Opinel, but I have reason to believe it’s pretty close, although there may be fewer Neanderthals involved. Not sure.

It’s interesting that Opinel knives are designed by folks of the same country that, in the late 1940s, gave the world the Voisin Biscooter C31 Convertible (I’m particularly fond of the wicker seats!).

At least Voisin had the good sense to upgrade the design of this “car” within the following decade.

Doesn’t this look much better? Now that is design advancement!

As a side note, it appears that there was some sort of medical condition going around in that part of France during the founding Opinel that made people very small. Our guy, JoeOp, was by some accounts, wasn’t a very tall man.

Neither was his son, Maurice, who took over the company once JoeOp retired.

This condition even affected some of their factory workers. They hired some very small men to do the blade sharpening on normal-sized grinding wheels, and those men did the job admirably.

Rather odd, isn’t it?

Opinel History, Version 2

OK, enough with the silliness (for now). The story of Opinel apparently begins as early as 1800 when the papy of JoeOp, Victor, set up an iron forge shop to make nails (someone had to do it, as Home Depot hadn’t been invented yet). His petit garçon, Daniel, eventually grew up, took over the business and began successfully creating hand-made, edged cutting tools. Finally, Daniel had a petit garçon of his own, our guy JoeOp, in 1872. JoeOp worked in the shop of his père for a bit, but like all such founder stories, he got bored. Unlike père Daniel, who believed the old ways were the best, which meant building tools and products by hand from a forge, our guy JoeOp was a tinkerer, a visionary, a man with machinery in his blood (that can be treated now with a round or 2 of antibiotics, you know). He wanted to create a new edge tool product similar to the kinds of tools his père, Daniel, had done so well, but take it to the next level by incorporating modern industrial manufacturing technologies and techniques emerging at that time.

However, père Daniel told him, “Non”, but JoeOp told his père to take a dive off of the top of the La Tour Eiffel, waved off his objections, and went forward with his plan. So at the tender and often reckless age of only 18, JoeOp founded his new company, naming it “Opinel” (I’m guessing he didn’t spend too much time on that one). He decided he’d make a folding pocketknife using modern industrial methods.

Was it the world’s first folding knife? Not even close! The oldest folding knife found so far comes from a dig done in an eastern Austrian village called Hallstatt. The Hallstatt Knife is a folding metal, Hawksbill-shaped blade (Karambits hadn’t been invented yet) attached to a bone handle sporting a blade edge groove cut, and a basic pivot supported with a metal bolster. The Hallstatt Knife dates back to approximately 500 to 600 BCE, a good 2,400 years before JoeOp and team began their work. Amazing!

Nevertheless, JoeOp began learning how to manufacture pocketknives at scale using modern factory methods. He quickly created a basic design that he dubbed the “simple working man’s knife” (aka “peasant’s knife”). Apparently, it was popular enough with the local workers (especially the winemaking peasants, who before they got their Opinels, had to harvest grape from vines the traditional way – by biting the stems with their teeth – at least that what I found doing some more of that informative online research!

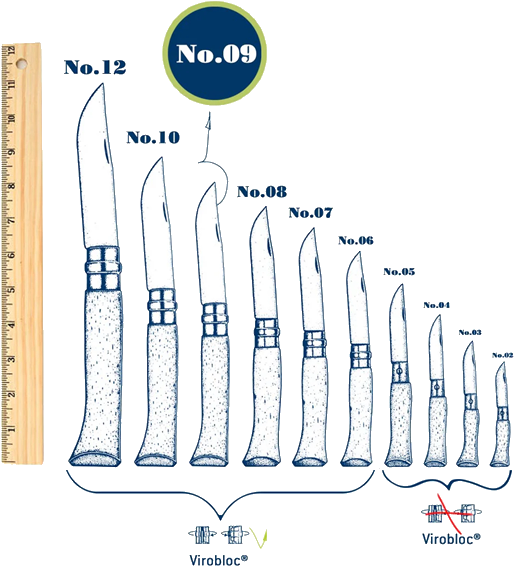

His design was also simple to build. By 1897, JoeOp had scaled and diversified his inventory by making a bunch of bigger and smaller versions of the exact same knife (diversification back then wasn’t very sophisticated) in 12 sizes, naming them No. 1 through No. 12 (again, like with the company’s bland marque, he didn’t really spend much time on a jazzy set of sobriquets for his knife models), and the business grew.

By 1901, he bid père au revoir and built his own factory. Slowly he expanded his operations, hired local peddlers to peddle, and peddle they did, and business continued to grow.

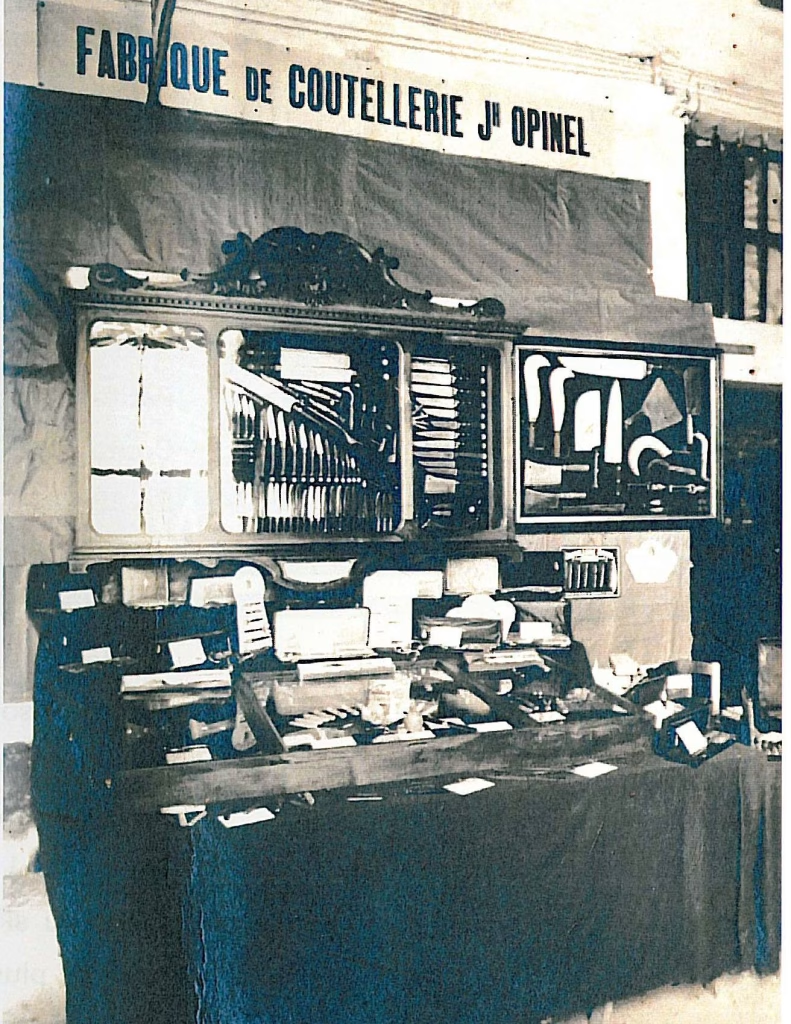

The true breakout for our guy, JoeOp, and his eponymous company came in 1911 at the International Alpine Exhibition at Turin, Italy. JoeOp brought his bag of goodies all loaded up in an exquisitely carved display case (our guy knew how to do marketing!). It was a beautiful presentation of his goods, enclosed in a beautiful, fine furniture-level display case. The Exhibition’s jury was impressed enough to award him the Best in Show (woof!) gold medal, and Opinel was now on the world map.

In 1915, he opened a modernized shop next to a railway junction. Railroad workers not only liked these knives, and word soon spread throughout the railroad network, boosting the business once again. By 1939, JoeOp had sold 20 million knives to Europeans across the continent. It continues to be a successful business today, as Opinel reported sales of 6.5 million knives in 2023.

And yet, Opinel’s core products haven’t materially changed since 1890. Go figure.

The undeniable truth of the matter is that Opinel has become the Coelacanth of the pocketknife industry. Every folding pocketknife maker today owes a debt of gratitude for the vision held by Mr. Opinel in 1890. Every one of them today stands on his shoulders for his original product designs. But that said, the Opinel knife and the Coelacanth are both “living fossils” of a bygone era. Yes, they are both still with us today, but neither ever evolved into modern, more sophisticated forms, as did all their contemporaries and successors. And as a result, both are outclassed and outperformed by succeeding versions of their kind that evolved over their spans of time. Ultimately, the Opinel and the Coelacanth are little more than current-day, archaic curiosities rather than modern entities in their respective classes, be it a fish or a pocketknife. We can (and certainly should!) praise them for their persistent longevity, but we’re still left surprised that they are still here.

Introducing the Opinel No. 9

The Opinel No. 9 is larger than the Opinels No. 1 through No. 8, but smaller than the Opinels No. 10 through No. 13. Do you see the clever pattern here? Mmmm-hmm. The numeric naming scheme definitely made taking inventory pretty simple. However, things are still confusing. There were 12 knife models as of 1897. But in 1935, both the tiny No. 1, a knife so small that mice were using them as surgical scalpels, as well as the longish No. 11, which was nearly as long as the No. 12, and yet nearly as short as the No. 10, so no one wanted it (weren’t all of these incrementally-sized knifes in the same situation?), were dropped from the line-up. Then in 2010, Opinel added the No. 13, an absurdly long novelty knife that has a 22.5 cm / 8.86” blade. That’s a whole lot of junk steel in one knife! So by removing the No. 1 and No. 11 and then adding No. 13, they now have 11 knives in their numbered lineup. Got it?

The original Opinel knife was pretty basic and easy to build. This is how (I imagine) the Opinel knife was built:

- Take a block of wood (Beech, to be precise), lathe haft into a cylinder, and then cut a deep slot down the length before stopping a few millimeters short from the end (JoeOp also invented the circular saw to make this cut!).

- Mill the haft so the height at the bottom end is a contoured pommel.

- Mill a contoured hand swell into the haft by narrowing the diameter at the top end, then cut the top section slot completely through.

- Mill the bottom-end sides of the haft to reduce its width (but not its height).

- Forge a narrow, thin piece of high carbon steel with a very short, rounded tang with a center hole.

- Install a slotted steel collar ferrule with 2 drilled holes placed 90° down from the slot on each side, onto the top end of the haft, aligning the ferrule slot with the haft slot.

- Drill the haft through the ferrule holes.

- Insert the blade tang into the ferrule-reinforced haft slot, aligning the tang hole with ferrule holes.

- Drive the axle through the holes and secure it in place by hammering the axle ends as rivet heads.

That’s more or less how an Opinel knife was built for 65 years (I’ve never built one, but this is my best guess. Heck, I hadn’t even held one until prepping for this article!).

In 1955, the blade locking ring, called the Virobloc, was introduced, which, by twisting the ring, prevented the open blade from closing by blocking the blade heel from moving, much to the gratitude of French hospital emergency rooms everywhere. It was only in 2000 that the Virobloc was updated to prevent the locked blade from opening when locked closed (progress in action!).

Today, the Opinel knife is still a favorite among those who ride pennyfarthings, use straight razors with shaving soap mugs and badger-bristle brushes, listen to music on Edison cylinder phonographs, use hand crank telephones on party lines, and watch baseball. Opinel still sells around 6,500,000 knives annually, earning €34,500,000! There’s apparently a lot of old timers, steampunks, and baseball fans out there.

Details and Specs

All seriousness aside, let’s get into the actual SharperApex review of the Opinel knife. Hold on to your bowlers!

Blade

The Opinel No. 9 Carbone uses XC90, a high-carbon, low-alloy steel that was probably considered a fine choice 135 years ago. It’s a very simple steel that only incorporates the elements carbon, manganese and a smidge of silicon into the base iron. It also unfortunately includes doses of both phosphorus and sulfur, elements that are considered unintended impurities and are detrimental to blade steel performance. The steel is easy to sharpen but is quick to dull. Best (or worst) of all, it has literally zero corrosion resistance, which means it’ll rust just by exposure to humidity in the air (knifemakers obfuscate this fact by stating carbon steels will “patina”. An old silver coin that acquires toning is what I consider a patina; carbon steel just gets eaten away by malignant rust). The most onerous part of the inevitable rust is how it forms on the Carbone steel blade tang underneath the haft slot at the axle pivot, where it can’t be cleaned. The already poor blade action becomes a tug-of-war with the resilient haft. This is ludicrous.

Opinel has been using carbon steel for 135 years. Some will say that this is tradition, maintaining the old ways. But adhering to traditions blindly aren’t always good. Old ways are commonly replaced for good reasons. For example, up until the mid-1700s, barbers used to perform surgery, tooth extractions, set broken bones and perform bloodlettings (all without anesthesia, of course!). In fact, the red-and-white stripes of a traditional European barber pole represents blood and bandages (Americans added a blue stripe to represent, um, the flag?). Should we go back to that long-standing, multi-century tradition again? The next time you visit a barber shop, ask them how many teeth they yanked last week! And see if they have a special discount for leeches as they cut your hair.

So using the same, now antiquated, blade steel for 135 years, for the sake of tradition, is preposterous. After all, it was JoeOp’s père Daniel who was the Luddite of the family. Our guy was definitely a modernist. If he were alive today, he would certainly be interested in maintaining the forward thinking he brought to the table when he started his company. He’d be using CNC machines, automating manufacturing processes, and using the most current blade steels available. He must be laughing at all of us. Or perhaps crying.

Can you imagine still seeing a Buck 110 with a 420HC blade for sale in the year 2099? That’ll be its 135th anniversary. Probably not. How about seeing Spyderco selling the PM2 in 52100 in the year 2145? Not likely! Instead, by then, I see Spyderco perhaps offering some sprint runs of the PM8 using version 3 of AetheriumCut, a new blade material invented by Larrin Thomas V, which uses a Tungsten Carbide Nano-Lattice microstructure with a hardness of 85+ HRc. And by infusing Shredded Titanium Microfibers throughout the blade microstructures, the blade will have an ultra-high toughness that cannot be chipped or broken by any amount of stress human strength can generate, including with any manual, handheld tools. This new blade material will include Vanadium-Tungsten-Nickel Nano-Crystals coated with Plasma-Infused Boron Nitride, a hyper-thin, self-sharpening coating that maintains a super sharp edge down to the molecular level, ensuring the blade’s edge retention remains incredibly high, thus eliminating any need for any types of sharpening at all despite decades of hard, daily use. Lastly, the blade’s surface Ceramic-Aluminum Oxide Hybrid Layer forms an invisible corrosion resistance barrier that protects the blade from all forms of corrosion, including oxidation, chemical corrosion reactions from extreme, prolonged exposures of saltwater, highly acidic or alkaline environments, and most forms of long-term nuclear radiation.) Yeah, now that Spyderco release will be interesting to me!

The Carbone blade comes quite sharp out of its zip-top baggie. If you enjoy factory-sharp blades, the Opinel will make you smile. And if you want to keep your Opinel Carbone blade that sharp, I have one simple piece of advice. Don’t use it. At all. If you cut anything or have anything hard touch the blade edge, your factory edge is gone, long gone. I used my digital calipers to carefully measure the blade height of the Carbone blade near the back, close to the handle (which I do for all knives I review). Just touching the blade to the calipers rolled the steel at that spot, and it was clearly evident when running test slices on 20# paper. In fact, with every slice in the paper I made, more rolled edges began to appear, this time near the Yatagan edge curve where more of the cutting was done. Seriously, the burr was easily felt by my finger. I used the blade to cut paper just 3 dadburn times.

I recommend keeping the nice factory edge intact by putting your Opinel knife into your kitchen junk drawer and leaving it there, occasionally finding it when you need a rubber band, opening it with both your hands (make sure you have a fingernail long enough, or that sucker is staying closed), look at it for a hot second, then close it, twist lock it, toss it back in and take your rubber band as you close the drawer. You’ll have a great edge forever (until the edge rusts away). If you don’t live in Death Vally or the Gobi Desert, which means rust is a problem, you can keep your Opinel knife deep inside a 5 lb. sack of dry rice. That will help a little bit.

XC90 Carbone TECHE

When I can get the ratings data for the knife steels I review (I primarily gather the data from the authoritative KnifeSteelNerds.com as available), I include it here in a new section I call TECHE. What does that mean? Well, just look at the table below.

Note that all but Hardness Range are based on a scale from 0-10; Hardness Range is based on the Hardness Rockwell C scale.

Also note that there just aren’t that many (i.e. there are zero) blade steel property ratings on Opinel’s XC90 or “Carbone” steel. I have collected a huge database of ratings and elemental compositions covering ~1,500 knife blade steels. There are no ratings there for XC90. So I narrowed the list down to other high range carbon steels that had practically the same composition as XC90. Many folks say that XC90 is similar to 1086, but that’s another steel with no available ratings. The only one that had ratings data was 1095, which is as compositionally similar to XC90 as it is to 1086 – extremely similar with just carbon, manganese and iron (XC90 differs only by adding a tiny amount, between 0.15 to 0.35 percent, of silicon), and all of them include impurities phosphorus & sulfur, just for funsies! As a result, I used the ratings scores for 1095 as a good proxy for XC90, and those ratings are distinctively unimpressive, unless you are looking for a blade that will erode away quickly under the abrasion of a good diamond stone or a mist of water vapor. Here’s the best data I can find:

| Blade Properties | Ratings |

|---|---|

| Toughness | 4.5 |

| Edge Retention | 1.5 |

| Corrosion Resistance | 0 |

| Hardness Range | 57-59* |

| Ease of Sharpening** | 10 |

* Hardness Range data was gathered from the Opinel website.

** Ease of Sharpening data is not a rating produced on KSN.

Blade Details

Opinel designates the blade shape as a yatagan, a type of knife used by the Ottoman Empire between the mid-1500s through the late 1800s. Think of it as a long, clip point blade angled slightly downward from the centerline of the handle. Ottoman yatagans were short swords or fixed blades, so this is a funky choice for the blade shape. The Ottomans never reached any farther west into Europe than the Balkans and Romania, and the Moors never got any farther east than Burgundy and Lyon, with raids extending into the Rhône Valley, so JoeOp’s homeland region in France was not directly influenced by Ottoman designs. Perhaps the shape just was a utilitarian choice, but it’s a curiosity why it’s modeled as an old, Ottoman blade instead of a straight-forward clip point. The only style element that makes it a Yatagan is the slight downward dip from the handle. Perhaps this feature is an artefact of the original knife design’s axle placement, where the blade spine didn’t actually reach a level placement with the back of the haft. It’s good business strategy to accept and adapt to a manufacturing error rather than try to fix it! It’s a feature, not a bug!

The blade has a nice machine satin finish with a distinct vertical scratch pattern. The blade uses a full flat grind but also uses a convex edge finish. It’s likely that the softness of the steel required this as a means to offer a bit more edge stability. A pure flat grind with no secondary edge bevel on steel as soft and thin as the Carbone would certainly cause it to roll over even more easily as it does today.

For all of us knife sharpening enthusiasts out there, note the absence of a sharpening choil. While the heel of the blade does extend down from the Virobloc, the Yatagan blade angle means that this blade will be difficult to sharpen on a stone with a reasonably stable edge angle without abrading the H-E-double hockey sticks out of the Virobloc ring. You’ll need an elevated stone with a clear and accessible edge (not sitting inside most stone holders), or better yet, a fixed angle sharpener. As a last resort, just use that crappy pull-through sharpener you got as a cheap holiday gift years ago (you know the one, sitting in your junk drawer; it sucks, does not effectively sharpen anything, but it does do damage to a blade!). This may be a strop-only blade for many folks.

Despite this knife being made so close to Italy, Opinel sadly foregoes adding a beautiful, Italian blade finishing-style of a softly curved, crowned spine in favor of just selling the Spyderco-style, 90° razor-edged spine edges that are practically as sharp as the once-used blade edge itself (and certainly more durable). Yes, adding a crowned spine would raise the cost of the knife a little bit, but this is already a very cheap knife, folks! Any cost increase for a nice feature would be well worth a small price bump, even if it’s not “traditional Opinel”. Another related, worthwhile upgrade would be the addition of blade jimping. The super-thin blade spine, harshly unchamfered as it is now, is an ideal candidate for adding a bit of thumb-saving, fine jimping. Hey Opinel, your neighbors at Viper Knives, who did a gorgeous blade spine jimping on my Viper Moon, can show you how it’s done.

The evenness of the Opinel blade edge is not that great, as the belly has a shallower edge than the main, straight edge – on both sides, so at least they’re consistent. Meh. What can you expect at this point?

It is said about Opinel blades that they are easy to sharpen. But be aware that you can go too far with that. I heard these were only sharpened twice each, and it was so easy, the person was left with these nubbins.

Lastly, let’s talk blade markings. Opinel makes quite an impression on its knives! Literally. On the “clip” side (aka the right side), there’s nothing. OK, that’s covered.

On the “show” side (aka left side), they added a deep-impression stamp into the blade metal, positioned under the spine, very close to the top of handle. It’s 2 lines of text, in which the top line reads, in all capital letters, OPINEL (just in case you were unsure). The 2nd line reads (on this knife model, anyway) CARBONE. It’s so deeply stamped that it appears to be inked, but a strong flashlight reveals it’s just shadow.

To the right of the stamped text is the company logo. The emblem was added in 1909 as part of JoeOp’s belated adherence to a royal decree made 344 years prior. It ordered all French cutlers to affix a unique emblem to their products to identify each cutler’s products (this is the equivalent of a brand name, but back in the Middle Ages, people didn’t know how to spell “brand name”, or anything else, really, so pictures worked better). I think he knew his French customers-to-be would be impressed with a French cultural reference (I keep telling you that he was good at marketing), so he created the now famous, crowned hand emblem and added it to all his knives.

To the uninitiated, the hand looks like some dude making a double-barrel finger gun à la Mississippi River Boat gambling dandies brandishing a pocket Derringer shooting at the underside of a monarch’s jewel-encrusted hat. However, there’s actually a more relevant, cultural connection at play.

JoeOp selected the “blessing hand” emblem, which relates to an ancient story that 3 fingerbones previously belonging (and formerly attached) to John the Baptist were nicked from Alexandria, Egypt and brought by a saint to the small French town nearest to where JoeOp was born (But a 2 fingers emblem? 3 fingerbones? Don’t ask me to explain.) The crown shooting target represents his location in Savoy, which a time long ago, was a duchy, which is a subdomain of a monarch’s realm. OK,… It’s all fairly confusing to me. I started reading about all this in Wikipedia, and went down a deep, disconnected rabbit hole of confusion. So that’s all I have to say about that.

Blade Dimensions

Let’s dive into the deets on the Opinel No. 9 (No. 9, No. 9, No. 9, No. 9, No. 9, No. 9, No. 9, No. 9… I’ve been wanting to do this the entire time I was writing this post!).

The blade measures 90.02 mm / 3.54″ long with a cutting edge of the exact same length. The blade height (the measure that literally put a dent into the edge’s soft steel) was measured as 18.74 mm / 0.738″ tall with a blade spine thickness of a mere 1.79 mm / 0.072″ (in this case, it should be call the blade spine thinness!). This next metric was hard to measure, but the edge bevel thickness came in at a whopping 0.23 mm \ 0.0085″. That’s super thin, which will be super slicey, but can the blade steel support that thinness? So far, I am thinking not.

HRc Rating

Opinel rates their Carbone blade steel to be in the 57-59 HRc. I no longer trust my crummy, little Leeb rebound hardness tester (I’m getting absurdly low hardness results and the calibration process doesn’t resolve it), so I have no viable data there to share. I wish I did have a way to test it, though, as this Carbone steel seems awfully soft to me.

Ironically, Opinel states the following about their No. 9 Carbone: “The carbon steel we use for our blades has excellent hardness, which guarantees optimal sharpness, easy re-sharpening, and great resistance to corrosion when properly looked after.”

Professional translation: “The carbon steel we use is a bit harder than the wood handle, or at least a pine wood handle, if we made one. It offers excellent initial sharpness, and you will maintain that excellent edge for as long as you don’t use it. And if you keep the knife in a very large bag of dried rice, you will minimize the amount of rust that will still eventually develop.” You’re welcome.

The softness I experienced (as did others on the web) makes it seem as though Opinel doesn’t really do a heat treat on its steel. Luckily, I found proof that they actually do heat treats – photographic proof on the Opinel website!

Opinel giveth…

Ah, but in another photo on the Opinel website, they apparently burn out any temper in the steel at the edge bevel with a really aggressive grinder sharpening process.

…and Opinel taketh away.

Opening Mechanisms

This one is easy. There’s 1 nail nick on the “show” (left) side of the blade. That’s it. And the blade is so low in the haft groove when closed, there’s no other way to open it. And give there’s no washers or bearings, just steel against wood with a clumsy axle pin through the tang hole (and yes, there is up-and-down pivot lash). This makes opening and closing the knife impossible to do with one hand. Crappapalooza.

Locking Mechanism

This one is also easy. It’s called the Virobloc, a high falutin name for a wide, rotating ring on top of the ferrule that you twist to deploy. The Virobloc is so difficult to twist that it also requires 2 hands to operate. The Virobloc’s rotated metal collar works by blocking the heel of the open blade from folding up while under heavy use and cutting people’s fingers off (and imagine how much that would hurt with a dull blade!). That was a much-appreciated improvement.

The original Virobloc, released 65 years after the release of the knife itself (that would be 1955 for those who don’t remember dates or math and stuff), only locked the open blade. Sometime around the end of 1999, Opinel introduced a redesigned Virobloc that was also able to lock the blade when in the closed position. It involved cutting a notch at the bottom of the slot in the Virobloc ring. They dubbed this invention Transport Security. (I say it was not needed for transport security, as the blade is bound up so tightly in the wooden haft slot that the inherent friction between wood and steel means it would never accidentally open. And when the blade tang finally gets rusty in the axle area, the user will need to do some weight training and take biotin to strengthen their nails to pull that blade out.) Finally, in 2016, to the apparent disappointment of many, Opinel redesigned the Virobloc again to only lock when twisting to the left, whereas in the past it used to lock the open blade by twisting in either direction. Whatever.

Knife Body & Scales

The standard handle – oops, I meant haft – is made from Beechwood blocks. They have them by the truckloads!

However, not everyone is a fan of Beechwood. So Opinel stepped up to the plate and now offers new alternatives to a Beechwood haft! Now you can get a handle made of… other kinds of wood! (Yay.) Here’s what wood hafts they offer (and some interesting facts about each):

Default handle:

- Beechwood is susceptible to warping, cracking & shrinkage when moved between dry and humid environments. Additionally, Beechwood isn’t as resistant to water, pests and rot as other hardwoods, making it a poor choice for outdoor use. Lastly, it’s not as strong as other woods, such as oak.

Alternative handles:

- Ash (not burnt wood, but from the Ash tree, although burnt wood sounds kinda interesting, doesn’t it?), is a wood with poor stability after exposure to moisture due to its low density.

- Birch is a wood that is more prone to warping or cracking than other woods, such as oak. It’s also susceptible to furniture beetle attacks.

- Black Oak, a softer wood, is more easily dented than other kinds of wood, and can be prone to cracking and warping after a prolonged exposure to moisture and humidity.

- Black Walnut is a wood that produces a toxic chemical called juglone, which can cause skin irritation, even when the wood is finished.

- Cherry is a softer wood and is prone to easily dent and scratch.

- Chestnut, a tree that is functionally extinct, has been wiped out by a fungus that has killed 99% of North American chestnut trees and is significantly damaging European chestnut tree populations.

- African Ebony, a very slow growing wood, is one of the most common illegally harvested woods, making its availability limited and expensive.

- Maple is sensitive to changes in temperature and humidity, causing it to expand and shrink, leading to warps, cracks & splits. It’s also prone to scratches and dents.

- Olive wood becomes saturated when exposed to water, leading to cracks and splits. It can also cause skin and eye irritation allergies in some people.

- African Padouk is a wood known for splitting and tearing, and for causing allergies that affect the eyes, skin and respiratory system.

- African Rosewood is a rare tree. The logging of rosewood can cause the remaining forest to dry out, leaving it vulnerable to fires and desertification.

- Sycamore is not a durable wood, as it’s susceptible to warping and twisting, decays easily, and its dust can irritate the respiratory system, causing coughing and vomiting.

- African Wengé, an endangered tree due to over-harvesting and illegal logging in the Republic of Congo, is brittle and splinters easily, which can cause persistent inflammation. It also can cause a skin irritation reaction similar to poison ivy.

It’s also worth noting that both oak and beech are classified as A1 carcinogens in humans, especially with exposure to their wood dust particles. These woods can cause cancer of the upper respiratory tract, lung cancer and Hodgkin’s disease. Birch, mahogany, teak, and walnut woods are strongly suspected of also being carcinogenic in humans and are assigned to the A2 classification.

The more you know…

Now to be fair, I searched very long and hard and eventually did find one example of a wood alternative haft offering on the Opinel website. They sell, in a specialty model, an FRN-resin-based material. That’s so… untraditional of them! Harrumph! So when are we going to get a solid titanium haft? Anatoly is waiting…

The above woods come in varying colors, based on natural pigments inside the dead tree’s cellulose flesh when they are cut down, sawn to bits, and then slathered with some sort of varnish or shellac (which is made from insects!). The hafts are all the same cylinder-based shape, just scaled up or down depending on the number model of the knife. Some folks who actually use these knives remove the factory varnish because it gets sticky and gummy in gripped a sweaty hand. But if your Opinel is just going to sit in your kitchen junk drawer, you need not go to all this trouble.

There are no scales, no liners, no stop pins, no springs, no pivot faces, no backspacers, no barrel spacers, no lanyard holes, no pocket clips, and no screw fasteners of any sort. However, the Opinel haft does qualify as having an integral handle. That’s cool, right? Well, it would have been, but instead of being made of single, solid chunk of titanium, this one is made from a piece of a broken broomstick handle (more or less).

Now there might be a glimmer of hope, way far out on the horizon. There have been a series of concept versions of Opinel knives designed for 3D printers by outsiders to the company, and the designs are getting interesting. However, they need to pay attention to ergonomics in the handle grip. Some of these are 100% for looks, not holding. Of course, they could do even better by doing a complete redesign of the handle grip shape! And the most important requirement is that they absolutely need to bring such a knife to a modern steel blade. The people inside the company need to take a cue from their user fanbase’s interest in having a modernized Opinel and delivering an updated product. We’re waiting…

Handle Dimensions

Let’s talk numbers.

The length of the Opinel No. 9 haft measures 118.22 mm / 4.655″, and the closed haft height came in at 24.56 mm / 0.967″, only slightly higher than the haft thickness of 22.03 mm / 0.868″ because the blade spine only stands proud by a mere 2.54 mm / 0.0995”. The pivot center-to-open-knife fulcrum balance distance is only 6.98 mm / 0.275″ down the haft, meaning the knife is very well balanced. But that’s all the handle metric data I have to report.

Hardware

The metal used in both the ferrule and in the Virobloc locking ring are of some sort of undefined stainless steel. There’s literally nothing else here to report.

Ergonomics

There is no finger choil nor any finger guard of any sort. However, the contoured hand swell of the central part of the haft serves to help keep the knife safely centered in the hand – as long as you keep a tight grip (maybe this is why they use a varnish that gets sticky and gummy in a sweaty hand!). The butt of the haft serves as an ersatz pommel, helping to keep the knife from being pulled out of the hand.

The overall ergonomics are not bad at all – if you only look at the handle. With that strict perspective, Opinels’ contoured hafts are better than most knives. However, the blade ergos are their colossal downfall. The absurdly sharp blade spine edges and the lack of jimping means that you really can’t work much with anything other than a basic hammer grip.

Lastly, don’t get me started again with the (profound lack of ) ease of opening or the requirement of using 2 hands to do any operation with an Opinel. To sum it up, the Opinel is not a knife that is ergonomically designed and manufactured. But I suppose that’s by tradition, huh?

Weight

The No. 9 knife weighs in at 54.72 g / 1.93 oz., which gives it a Weight-to-Blade-Length Ratio of 0.61, a ridiculously low number. It’s not a bad thing, mind you (unless you like a bit of metallic beef on your knife). It just means that the ratio of 1 oz. per 1” of blade is blown out of the water by the incredible lightness of this knife.

Original Packaging

OK, I’m not even sure if what I have to say is valid, except for the fact that I bought my Opinel No. 9, along with 2 other knives that I plan to review in the coming months, from KnifeCenter (DCA’s hangout). The other 2 knives came in their expected telescoping boxes or nylon zipper pouch. The Opinel, on the other hand, came in a zip-top baggie. I kid you not.

Is this standard fare packaging for Opinel knives? Did DCA and SethV accidentally burn all the Opinel boxes in a warehouse mishap involving nitrous oxide gas and Thomas’ beater pick-up truck? (Don’t ask me how I heard about this.) On the other hand, if this is how Opinel saves money to sell their knives at a lower price, there’s something to be said for that. And what I’ll say is that as brand first impressions go, this one was an atrocity.

Knife Karen Nitpicks

Let’s get right to the point. I REALLY need to speak to the manager about this one! JoeOp, where are you when we need you?

- The knife design is 135 years old; it looks like it and performs like it.

- Hey Opinel, turn off your oil lamps, get off your chamber pots, empty out your ice boxes, stop using washboards for your laundry, put away your carpet beaters and listen up. This is no longer 1890. That time has passed. Open up the Internet (oh, crap, how do I explain the Internet to a true supercentenarian who thinks pennyfarthing bicycles look futuristic?). Um, well, um, just go talk to someone outside of your factory and learn about the modern wonders of our world today. Sheesh.

- The handle haft is little more than a broken-off piece of a broomstick.

- The Carbone blade steel is as malleable as a metal marshmallow and fights rust like Mike Tyson fought Jake Paul.

- Hey, Mr. Tyson, I’m just making a silly joke! We’re still good, right? Aren’t we? Mr. Tyson? Speak to me, Mike! Oh CRAP!

- The zip-top baggie packaging is as impressive as last month’s tuna salad sandwich left in the trunk of your car. In July.

- It has an integral handle – made of wood.

- It can only be opened with the 1 nail nick and requires 2 hands for opening, closing, locking and unlocking.

- The washerless & bearingless pivot axle works with heavy wood-on-blade-tang friction.

- When the blade tang begins to rust, your problems just got significantly worse.

- The blade spine edges are sharper than the blade edge dulled with rollovers after cutting a couple sheets of paper.

- The only way to keep the blade factory sharp is to never cut anything with it.

- Sharpening the blade near the heel without severely scuffing the Virobloc is needlessly difficult.

- The company logo is confusing, looking like a double-barreled Derringer finger-gun shooting a king’s hat.

Price

Folks, the Opinel No. 9 Carbone is a $20 knife. I know we shouldn’t expect much from such a knife, but in my previous post about the Harbor Freight Budget Knife Fight, we see that some budget knives can be a much better value than this antiquated remnant of history, for just a few dollars more.

Verdict

The Opinel No. 9 Carbone knife is a contraption right out of history. It was designed 135 years ago and has remained largely unchanged ever since. In fact, the Opinel No. 8 is the oldest, continuously built knife model that is still sold today! The other Opinel numbered series of knives are design derivatives of the original No. 8. Joseph Opinel, the founder of the company, came from several generations of metal workers who created iron-based products on a forge, ranging from basic nails to edge cutting tools. Our Mr. Opinel was interested in the path of his father and grandfather, but he was also a modernist, a visionary, who wanted to manufacture such products using the latest industrialized manufacturing machinery and techniques so he could create fine products at scale. While his father did not approve of his son’s ideas, Joseph went ahead, deciding to make folding knives as his product of choice.

His design was quite basic: it consisted of a mere 4 parts: the wooden haft (what we now call the handle) with a slot cut down one side, a thin and narrow carbon steel blade, a steel axle that connected the blade to the haft through a hole in the blade tang, and a metal ferrule that acted as a supportive bolster for the haft as well as a reinforced connection for the blade tang to the haft axle. His knives were easy to manufacture and equally easy to sell.

Joseph was an excellent marketer of his products. He upgraded his factory, he added an emblem that appealed to local pride with a reference to the town’s storied history, and he took all the best examples of his company’s work displayed in an ornate display case to an international exhibition where he was awarded the Best in Show gold medal. He used this as just another steppingstone for building his company’s reputation and brand awareness.

This all sounds really great, doesn’t it? Hmmm…

Opinel likes to boast that “Little has changed…” with their knives over the past 135 years. But that’s not actually a boast. That’s more a confession of guilty negligence and indifference to their customer market.

The numbered series of knives (from No. 2 through No. 13, except that No.11, and for that matter No. 1, both of which were discontinued back in the 1930s), still use the same blade design and materials as the original, and given its age, it looks much more like a relic from history than a modern pocketknife. It’s as if the Model T was still being sold right next door to a BMW dealership. You can almost feel a sense of vicarious embarrassment.

The blade is made of XC90 high-carbon, low-alloy steel, a very basic steel that only incorporates 0.9% carbon, 0.3% manganese, 0.25% silicon, with the base iron element. Oh, yes, there’s also phosphorus and sulfur, both of which are considered unintended impurities that most steels have long eliminated, as they are detrimental to the performance of the blade. And speaking of performance, the archaic XC90 as a choice of blade steel in the current world of modern steel metallurgy is ludicrous.

In terms of steel performance factors, in the toughness category, XC90 ranks at 4.5 out of 10 – sub-par mediocre, but not fatally bad. But that’s as good as it gets.

Edge retention ranks 1.5 out of 10. A properly heat treated high-carbon steel is too soft to hold a sharp edge for long, so it requires constant stropping and sharpening to have a useful edge. And a properly heat-treated carbon steel, as Opinel claims for their XC90 blades, is 57-59 HRc. Unfortunately, the Opinel XC90 carbon steel has a reputation for being unusually soft, with some claiming the hardness is actually in the low-to-mid 50s, which would negatively affect edge retention. The blade softness accusation reflected my experience when testing the cutting edge. The Carbone blade is just too soft to keep a sharp cutting edge, as the edge rolled over very quickly when cutting single sheets of paper. XC90 is quick to sharpen, but it’s equally quick to dull again.

Then there’s the issue of corrosion resistance, especially oxidation. XC90 ranks an absolute 0 out of 10. It’ll rust just from humidity in the air. While you can do your best to keep the soft blade steel oiled up, the real problem is when moisture causes the blade tang to rust inside the wood haft’s slot, where it’s held in place by the rivet-headed axle rod passing through the steel ferrule. And ever since 1955, when Opinel added a steel locking ring over the ferrule, it became all but impossible for most folks to disassemble their Opinel knife to resolve the otherwise unreachable, rusty blade tang.

Lastly for the blade, there is only 1 opening method on this knife. It has no thumb studs, no flipper tab, no opening hole, nor any blade lock assist. The Opinel knife only has a small, single-sided nail nick. That’s all. It takes 2 hands to open it, and 2 hands to close it (assuming one used the super-basic, twisting lock ring blade lock). And due to the steel-on-wood blade action, the friction is already pretty high (this blade has no drop at all), but that friction will get exponentially worse when the blade tang rusts.

Otherwise, unlike modern pocketknives, there’s no pocket clip, no backspacer, no lanyard hole, no scales with fasteners to dissemble the knife for cleaning & maintenance. But in that respect, we can celebrate that the haft is a genuine integral. Well, instead of being a titanium integral, it’s an integral made of little more than a broken off piece of a broom handle. Meh.

The design of the Opinel knife is a classic. In 1890, it was a top-of-the-line product built with good materials using modern industrialized processes. Cool! But that was 135 years ago. The world has changed enormously since then. Even the traditional American standard knife-makers Buck and Case are now making knives with modern super-steels, incorporating modern handle scales with screw fasteners rather than pinned construction. They offer modern blade opening methods, modern locks, pocket clips and modern styling (well, for Buck and Case, anyway). You can still buy (if you really want to) the old-fashioned Buck 110 or the Case XX slip-joint Jack knives if that’s what you want, but thankfully they offer the modern knives as well. Even Opinel customers are taking to designing their own 3D-printed handles to replace the antiquated wood hafts with modern materials and design sensibilities. But the Opinel company seems inextricably mired in 1890, as if the original knife design is somehow an inviolable tradition from which they cannot escape.

In the introduction to this article (so far back!), I said I wanted to test my old assumptions that the Opinel pocketknife is little more than a cheap wooden dowel handle with a soft, rust-prone blade. I happily acknowledge that the Opinel is very much an important historical artifact in the development of modern pocketknives. It’s a genuine throwback to the way pocketknives used to be. Unfortunately, its antiquated, 135-year-old design and the archaic materials used in the knife make it little more than a novelty to most modern knife aficionados, aside from a few pennyfarthing fanboys who, for reasons unknown, love that old stuff to the exclusion of all else. I honestly have no idea why. After handling, thoroughly examining, and working with the Opinel No. 9 Carbone, 19 years after my first encounter, it still has no appeal to me. Enjoy! ![]()