I saw Seth V of KnifeCenter do their New Knives of the Week video a few weeks ago and one of the knives he showed us was what he called a “Funny Folder” knife. I was not familiar with that term, but he showed us a beautiful, little Czech-made knife by Mikov s.r.o. called the Kostka (“Cube” in the Czech language).

I was intrigued by the little thing that looked more like a shiny puzzle toy than a pocketknife, so I bought one to see for myself how it worked. Little did I know that this knife design, while new to Mikov (and me!), actually dates all the way back at least to the end of the 19th century!

Let’s take an in-depth look at this latest interpretation on the Funny Folder knife.

TL;DR

The Mikov Kostka is a new riff on an old school knife design. It is a non-locking, little pen-knife-like folding puzzle whose small, clip-point blade is completely enveloped within the twin-loop handle when closed. It is curiously marketed by Mikov as some sort of ladies’ knife; one that specifically won’t stress or damage our nails. Hmmm. Do you suppose they assume women aren’t supposed to be interested in carrying thumb-stud-equipped, liner lock knives with full-size, compound-grind, shiny DLC-coated, crowned sheepsfoot blades and contoured, chamfered and anodized Timascus scales? If true, as the Knife Karen, I’ll have to speak to their manager about that!

The dainty Kostka is very much a stylish, pretty, mirror-finished novelty item, but in truth, that’s about it. As an actual, functional pocketknife, I think it leaves quite a bit to be desired.

Pros

- Beautiful design

- Compact size

- Mirror finish

- Chamfered edges along all sides of the knife body

- Quality knife-crafting work

- Fun, puzzle-like folding body

- Relatively inexpensive

- Not supposed to damage our fingernails!

Cons

- Very low-end steel (440A)

- Very low hardness rating (55-57 HRc)

- Not sharp out of the box

- Mirror finish is an awful fingerprint magnet

- 2-handed opener (or requires slow, dexterous hand skills to be opened 1-handed)

- Hinged swivels connecting the body loop sections to the blade are too loose

- Non-locking, folding body makes the open knife’s handle feel unstable

Tech Specs

Brand | Mikov |

Website | |

Manufacturer | Mikov s.r.o. |

Origin | Mikulášovice, Czech Republic |

Model Reviewed | Kostka |

Designer/Design | Mikov inhouse |

Model Launch Year | 2023 |

Style | Flip Flop Folder (aka Tri-Fold, Easifold, Funny Folder, Swing Blade, 3D Folder) |

Lock Type | Non-locking |

Opening Type | Manual |

Opening Mechanism(s) | Hand-operated 3D unfolding |

Pivot Type | Hinged swivels (not a traditional pivot opener) |

Pivot Mechanism | Washers |

Length Closed | 76.55 mm (3.01″) |

Length Open | 141.45 mm (5.57″) |

Weight | 39.39 g (1.39 oz.) |

Original Packaging | 4-color printed straight tuck end (STE) folding carton with side hang tab |

Edge | Plain |

Shape | Clip point |

Material | 440A |

Hardness HRc | 55-57 |

Blade Length | 61.80 mm (2.43″) |

Cutting Edge Length | 51.86 mm (2.04″) |

Height | 9.66 mm (0.38″) |

Thickness | 1.97 mm (0.08″) |

Main Bevel Edge Thickness | 1.15 mm (0.046″) |

Finish | Mirror |

Features | Ground across diagonal corners of a steel rectangular prism |

Grind | Full, flat grind |

Swedge | None |

Jimping | None |

Blade Markings | Show side: Company name |

Sharpening Choil | No |

On-Blade Opening Assists | None |

Materials | Stainless steel (440A?) |

Color | Mirror-polished steel |

Scale Thickness | 2.04 mm (0.08″) |

Scale Texture | Smooth |

Handle/Scale Features | Puzzle design, smooth 360° pivoting action, chamfered edges |

Handle Length | 76.55 mm (3.01″) |

Closed Handle Height | 11.15 mm (0.44″) |

Handle Thickness | 11.18 mm (0.44″) |

Pivot Center-to-Open-Knife Fulcrum (0.0 is balanced at pivot) | 24.37 mm (0.96″) |

Integral Handle | No |

Lanyard Mount | None |

Pocket Clip | None |

Fasteners | None |

Who is Mikov s.r.o.?

According to their website, Mikov s.r.o. is a company whose history goes back to 1794, when an industrious fellow named Ignaz Rösler in the northern Czech border town of Mikulášovice opened up his new factory to make knives, as well as pipe heads, files, sickles, scythes and tobacco pouches. The business of Mikov s.r.o. has evolved over the years and has also produced, at one time or another in the past, such products as aluminum foils, rolled wire and staples.

In its current incarnation, its operation has expanded to also produce office equipment, hole punches, staplers, staple removers, quick binders, magnetic boards, key & cash boxes, letter clips, scissors, pen sharpeners, snap-off knives and wall shelves. The company is a top producer of kitchen cutlery, brads and pins for use in upholstery, joinery, carpentry and the carton industry used by both mechanical and pneumatic guns. Today, Mikov s.r.o. is the largest maker of both office equipment and knives in the Czech Republic. Can you imagine an Epson tanto folding knife or a Spyderco document scanner? I’m intrigued by the notion.

The History of the Funny Folder Knife Design

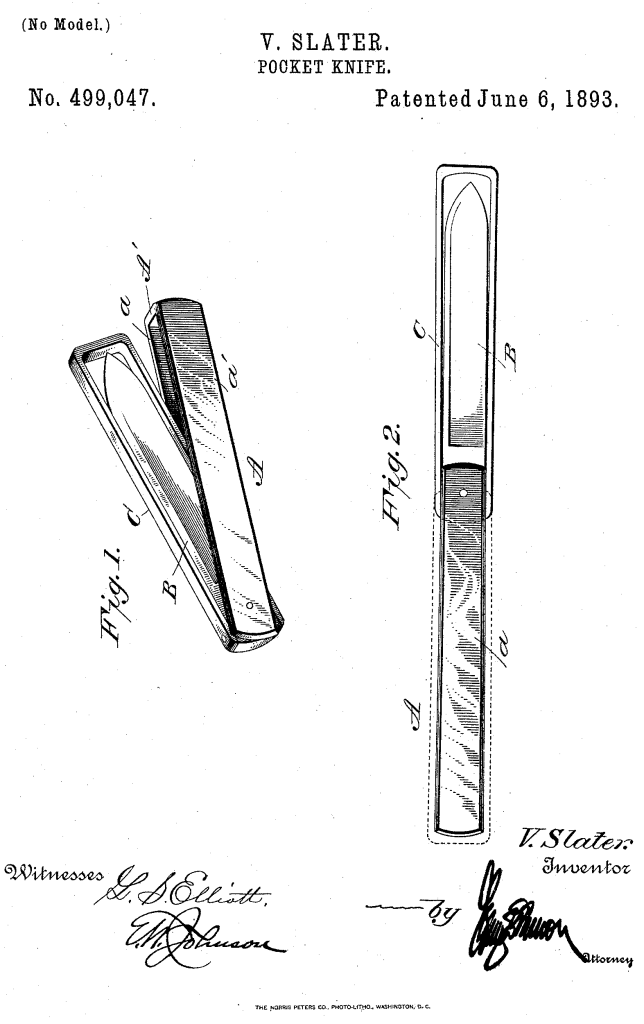

On their website, Mikov asserts that the Kostka is “an elegant knife of an original design and opening mechanism”. While that’s true, it’s just not Mikov’s original design or opening mechanism. The classification of this design of knife, using 2 perpendicular swiveling loops to both fully envelope the blade when closed as well as serve as the knife handle when the blade is exposed, dates back at least as far as a design patent (No. 499,047) granted to Mr. Vandalia Slater of Hunts, New York on June 6, 1893.

His patent application, which only identified the knife design as a “new and useful Improvements in Pocket-Knives”, described it as such:

“This invention relates to improvements in tool handles, especially designed for pocketknives and similar implements; the object of the same being to provide a handle or blade-guard in which there is the absence of the usual springs, the blade or implement when folded in the handle being thoroughly protected; and the invention consists in providing the blade or implement, which is pivoted to the handle in the usual manner, with a loop adapted to be swung over the handle to hold the blade rigidly extended, and also fold within the handle with the blade to protect the same…”.

At some point, many folks began to call Slater’s design the “Flip Flop Folder”. This design of pocketknife became popular because it could be cheaply made, and as a result, it saw its greatest proliferation as a promotional item, where the flat, broader handle loop could be engraved with the name of a company and sometimes its location on it. Those Flip Flop Folder knives were very commonly sold or even given away for business marketing purposes during the 1st half of the 20th century.

In the 1930s, the William A. Bailey company (WMBCo.) released a knife using this design that they called their Tri-Fold. It seems the Tri-Fold models were not the advertising knives like earlier versions, but were more personal knives, as people had their names engraved on them.

In the 1950s through the 1960s, the John Watts company in Sheffield, England, introduced this design in the UK (and possibly exported them internationally it seems), calling it the Easifold knife. Like the Flip Flop Folder, it was an inexpensive knife and featured advertising or promotional information on the handle, along with John Watts company branding.

In the 1970s, T.M. (Ted) Dowell, founding member and former president of The Knifemakers Guild, was given such a knife (probably an Easifold) and he was inspired to create his custom take on the design, which he dubbed the “Funny Folder” knife. He upgraded the materials and craftsmanship of the older versions of Flip Flop Folder, Tri-Fold and Easifold knives to produce a small number of much nicer knives in varying styles and sizes, including a beautiful, double-edged, mirror-polished, dagger version with Sambar Stag scales.

In the 1980s, Smith & Wesson offered their own version of this knife design called the Funny Folder Dagger, model KLC14782.

In recent years, this knife design has re-emerged once again, coming in a variety of names, with several Chinese brands leading the way. The A.G. Russell brand released their Funny Folder knife with a VG-10 Wharncliffe blade and an engraved, anodized, titanium handles.

The Rough Rider brand sells their version called the Pocket Trooper Swing Blade dagger in 440A.

Baladeo sells its Flip System knife with a hollow-ground blade simply identified as “stainless steel” (that’s never, ever a good sign, but it’s probably no worse than 440A).

The Benchmark brand offers their version of a Funny Folder that they call the Paratrooper knife.

It looks a lot like the Kostka, doesn’t it? It’s nearly identical, in fact, including the cubic shape of the blade tang (minus the glass breaker tip) and the use of low-end, 440A blade stock. But the Paratrooper has apparently been for sale since 2018! So much for the Kostka being Mikov’s original design!

The Paratrooper name, though, is a weird anachronism of sorts that someone in Benchmark screwed up. In WW2, the German Luftwaffe provided their paratroopers with a very interesting folding knife that encapsulated the closed blade, although it was not the Funny Folder design.

Instead, the Germans gave their paratroopers a pantographic-style knife in which a scissors-like-action handle design covered the blade when closed, but also became the handle when the knife was opened. Research your historical references more thoroughly for your knife design names, Benchmark!

Lastly, a high-end, tactical version called the Nomad Swing Blade offers a 4”, stone-washed AEB-L Tanto blade and titanium handles, all for a mere $299! What would Vandalia Slater think of that?

Introducing the Mikov Kostka

The Mikov Kostka is a lovely little piece of highly polished, low-grade steel that unfolds in 3 dimensions to reveal a little blade inside. It’s pretty when folded, and definitely remains so once opened. If you are looking for a beautiful, highly polished steel puzzle knife-like object, and you will wear gloves when handling it, and you really don’t intend to cut anything with it, then you will very much enjoy the Kostka. It might even save your nails (although the glove will help more with that).

But if you are looking for a small knife that you can carry that will reliably cut when needed, not always look smudged and dirty, not have the blade edge roll and dull almost immediately after the first cut post-sharpening (if you can get it sharp), and feel sturdy in your hand, then you might want to read on. I’m not sure the Kostka is the knife for you.

Details and Specs

Let’s take a serious look at the Mikov Kostka for what it is supposed to be – a small pocketknife rather than a shiny piece of purse or pocket jewelry.

Blade

The Kostka blade is crafted from 440A stainless steel. Hooray, it won’t rust! But it also won’t cut much, either. 440A was invented in 1926 by David Giles, a metallurgist for Latrobe Steel in Latrobe, PA as an upgrade from older 304 and 316 stainless steels. Back when it first came onto the market, 440A was considered so much better than its predecessors that folks called it “razor steel”. That’s more of a blistering commentary on the mediocrity of those previous steels than praise for 440A.

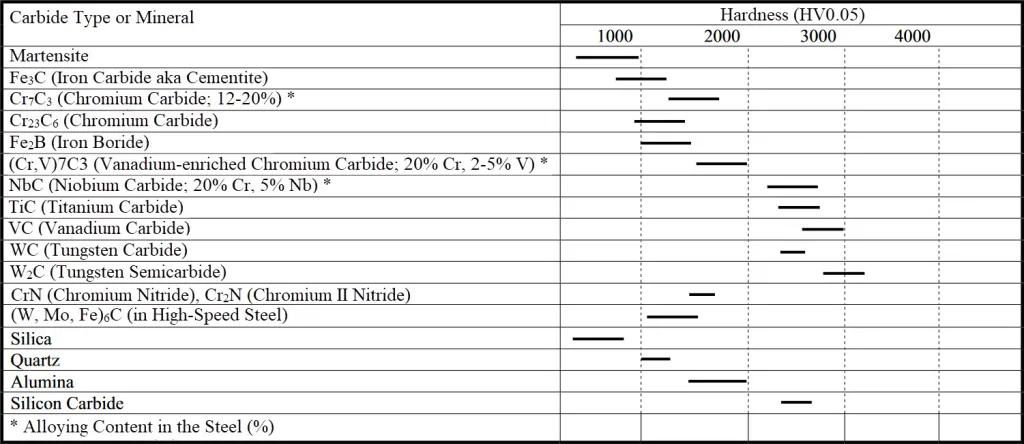

3 Key Blade Steel Properties – Pick 2

Well, 98 years goes by so quickly these days. In those bygone days of yore, the most common steel used in knives was basic carbon steel. Carbon steel could be very tough, and could be sharpened to an extremely fine edge. Unfortunately, because the older steels were not very hard, the blades dulled quite quickly as they didn’t have the metallurgical advances we take for granted today to make them hard and keep them sharp. Much of the problem was the research and technology of steelmaking had not yet fully developed. There’s so much here that could be discussed, but those details will have to wait for a later post (or 2 or 17 or whatever).

That said, there are 3 important properties against which all blade steels are rated, and often these properties conflict with one another. The properties include:

- Toughness: Resistance to fracturing or chipping; brittleness

- Edge Retention. Resistance to wear from abrasion; how long the edge stayed sharp

- Corrosion Resistance. Resistance to damage from oxidation and other factors; rust

Traditionally, this has meant that a knifemaker could pick 2 out of the 3 properties they wanted their blade to emphasize, and the 3rd property was always the one compromised.

Early Stainless Steels

The beginning of stainless steel goes as far back as 1798 when scientific work began investigating the properties of chromium (Cr). Subsequent work included how the properties of iron and steel changed with the addition of Cr, specifically how it inhibited the formation of oxidation – aka rust. The first martensitic stainless steel, which can be heat treated to improve its mechanical properties, was invented in 1912 by adding significant amounts of chromium (up to 20%) to the alloy.

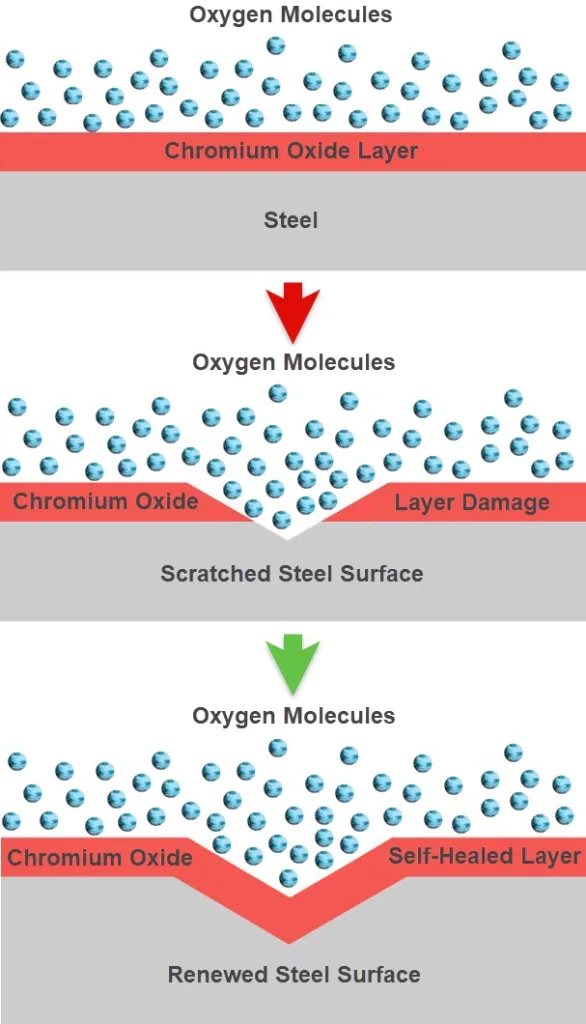

Cr not only improved steel by hardening it, Cr improved its corrosion resistance property by reacting with oxygen atoms to form a microscopic, “passive” layer of chromium oxide (Cr2O3) on the steel’s exposed surface, which blocks the steel’s interaction with corrosion-inducing oxygen. Even when scratched, stainless steel’s Cr2O3 outer layer is self-healing and is re-established in the presence of oxygen.

However, large amounts of Cr were needed to make steel stainless because Cr tends to precipitate out of the molten steel into large, relatively strong chromium carbide particles, so steel manufactures had to add enough Cr to ensure it remained present in the non-carbide steel matrix so it could form Cr2O3 on the steel’s surface. The appearance of hard chromium carbides was good, as those particles improved a blade steel’s edge retention property. Unfortunately, large amounts of Cr also had a negative side effect: it made steel more brittle, reducing its toughness property.

Conventional Ingot Steel

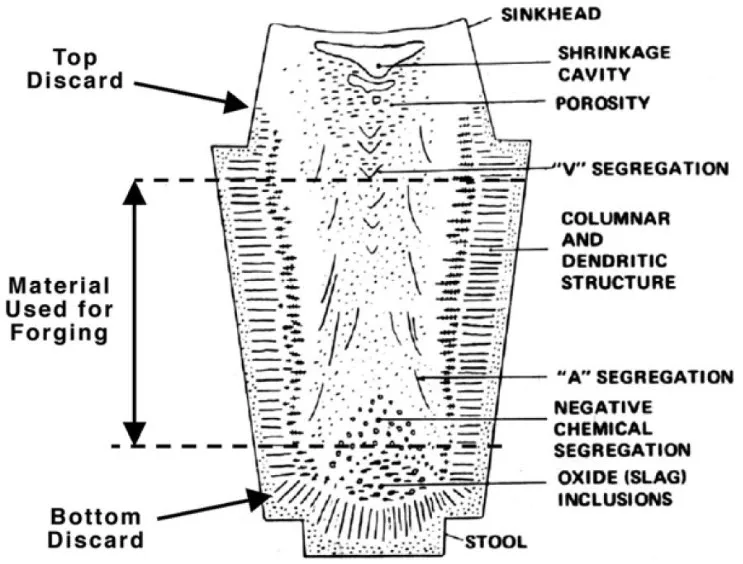

Older steel manufacturing technology had mills pour molten alloy into large molds that formed slow-cooling ingots. The problem was that the time needed for the ingot to cool, especially given the uneven cooling of the ingot’s surface versus its interior, allows for the steel alloy elements to segregate out of the uniform matrix, creating a coarse crystalline (called grains in steel metallurgy) microstructure, especially in stainless steel.

These large grains reduce toughness in steel because stress cracks typically form and propagate along the boundaries of the large grains, also making the steel more brittle. Large amounts of Cr made stainless harder, but more liable to fracture more easily. Brittle steels are susceptible to not only suffering catastrophic breakage, but under stress, experiencing significant, microscopic chipping along the thin blade edge as well. There are processes that blade manufacturers can do to their ingot steel to somewhat mitigate the elemental segregation, and thus help in a limited way improve the low toughness, but it can’t be fully eliminated in ingot steel.

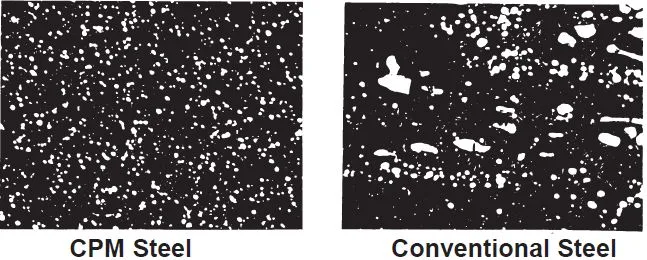

Particle Metallurgy Steel

Many of the stainless steels in use today are based on modern manufacturing technologies, such as Crucible Particle Metallurgy (CPM), a metallurgical manufacturing method that addresses the inherent weakness of slow cooling, coarsely structured, ingot steels. CPM steel (and similar “powder metallurgy” steels from other manufacturers) is created by passing molten, liquid steel alloy through a high-pressure spray nozzle into a nitrogen-filled chamber. The spray process allows the steel to quickly cool into a uniform powder of tiny, spherical droplets of metallic micro-ingots that do not suffer from the segregation of the alloy elements. The resulting steel powder material is then added to sealed containers that are heated under pressure to bond the particles into a homogenous, solid ingots with a uniform, very fine microstructure, ensuring the carbides in the steel are small and evenly distributed throughout the matrix.

The development of particle metallurgy steel manufacturing 50 years ago by Crucible Industries has completely revolutionized the quality and utility of steel products available today.

Reduced Chromium Stainless Steel

On top of that, there are very new metallurgical stainless-steel products, such as CPM MagnaCut, that changed the way Cr is distributed within the particle steel matrix. Chromium carbides are hard, but not as hard as vanadium and niobium carbides, a preferred substitute for improved edge retention.

Chromium carbides can also be pretty large, which, as mentioned above, is detrimental to steel toughness. So the inventor of CPM MagnaCut, Dr. Larrin Thomas, reduced the amount of Cr to improve edge retention (wear resistance) but still maintain corrosion resistance, reduced the amount and narrowed the range of acceptable levels of carbon to retain hardness but ensure chromium carbides would dissolve at a lower heat treatment temperature, and ensured that both vanadium and niobium were in the alloy to get their far-harder and smaller carbides (compared to Cr). He figured that by specifying how the heat treatment for MagnaCut would be applied, it would melt the formed chromium carbides so that all the available Cr would be available “in solution” within the steel grain matrix microstructure to provide the stainless properties he desired.

Sitting Firmly on the 3-Legged Steel Property Stool

Dr. Thomas created the first steel designed specifically for knife blades that was a finely balanced, strong performer in all 3 steel properties: toughness, edge retention and corrosion resistance. It remains the only knife steel that is so well balanced and such a strong performer across all 3 properties. Indeed, MagnaCut has proved to a revelation in steel metallurgy. Its hardness rating is typically regarded as being between 60-65 HRc (which is impressively high), and most unusual, its toughness property is not significantly compromised when the full heat treat cycles for maximizing hardness are done, including post-heat-treat, cryogenic treatments (aka it doesn’t quickly become brittle as it’s made harder). CPM MagnaCut also is impressively easy to sharpen, even at maximum hardness, given all those other, competing properties. And despite having less Cr than what the books say is required to be called stainless steel, MagnaCut has one of the highest corrosion resistance property ratings of any knife steel available today.

440A

Unfortunately, 440A stainless steel has a significantly low rating for both toughness and edge retention properties. It doesn’t help that 440’s hardness range is a mere 55-57 HRc, making it one of the softest steels still used on modern knife blades. Its corrosion resistance property is excellent, but otherwise, 440A is an old, very inexpensive form of stainless steel that should be retired as obsolete.

The hey-day for 440A steel has long passed, and yet, this antiquated, curiously brittle and simultaneously soft steel, is what Mikov selected for use in the Kostka. Perhaps it’s seen as a traditional Flip Flop Folder knife steel. I say check out the more modern steel options from A.G. Russell and Ted Dowell!

The Kostka’s clip point blade comes in a very pretty, mirror-polished, full flat grind with a relatively tall (shallow angle) secondary edge bevel. It has minimal blade markings, with only the brand shown on what is traditionally the show side, while the opposite side (there is no clip) is absolutely clean. It also came quite dull. Even if used just as a letter opener, cutting open a plain white paper envelope from underneath the sealed top crease, it needed some push. It tore the paper as much as it cut.

The Kostka blade has no jimping, no swedge, no compound grind, no sharpening choil, just a mirror finish that you hardly ever see because it is perpetually smudged with many layers of oily, grimy fingerprints from just opening it.

One interesting aspect of the Kostka is that the blade is cut from a rectangular block (not a cube technically, but instead a rectangular prism) of steel, and the blade is ground along a diagonal cross-section. I will say that the crafting work done here is beautiful, as the blade spine retains the original 90° rectangular prism side edge and the blade edge perfectly aligns with the opposite edge (where a sharpening choil might have been). The Kostka is a genuinely beautiful piece of knifemaking, even if the resulting knife itself isn’t all that good.

Blade Dimensions

The blade is about 2 7/16” long with a cutting edge of just a hair over 2”, is about 3/8” in height, and has a slender thickness profile of 5/64”.

HRc Rating

Mikov states that the Kostka in 440A has an HRc hardness of 55-57. That’s some of the softest steel still being used today for pocketknives. What was impressive in 1926 leaves a huge amount to be desired for any sort of working knife in 2024. Alex Garland, the excellent knife content creator of YouTube channel OUTDOORS55, recently did an excellent analysis on why some knives simply can’t be made hair-whittling sharp (spoiler alert: it’s because of very soft steel, and the example he demonstrated was, you guessed it, 440A stainless at 55 HRc).

Knife Body & Scales

Because of its funny folding design, the Kostka doesn’t have a traditional handle and scales.

What it does have is a couple of equal-sized, U-shaped loops that attach to perpendicular faces of the squared blade tang. One loop attaches higher on the tang than the other, and because both loops have wider gaps in the U portion than the thickness of their metal widths, they swing freely in 360° circles around each side of the blade. When they are aligned within one another, they either conceal the blade or reveal it and serve as its handle. The loops are nicely chamfered along their edges, so they are comfortable to touch.

That’s cool. But that’s it. The loops are also mirror finished and gunk up with greasy fingerprint goo super-fast. What was a beautiful mirror finish before you touched it quickly becomes a terribly unsightly thing afterward. I also found that, while the loop connections to the blade tang are nicely solid, because they don’t lock, the loops want to continue to slide around in your hand as you grip it, making the knife grip feel rather unstable and sloppily loose at the bottom end of its ersatz handle.

Opening Mechanism

The opening mechanism is your fingers and your brain to figure it out! But in truth, it’s not that hard of a puzzle. You swivel the outer, lower loop 180°. Then you swivel the other loop the same way, 180°. That’s the trick, folks. And it’s a 1-trick pony. That’s all there is. You’ll typically use both hands to open it, but if you want, you can do it one-handed. It’ll take a bit of hand dexterity and a lot of time, knife-opening wise. But don’t worry about hand safety. The knife isn’t very sharp.

Ergonomics

Ergonomics? Meh. It’s a narrow rectangular prism handle. It’s very small in your hands. If you press on the blade spine with your thumb, you feel that wiggly, slide-y loop instability I mentioned above. How much ergonomics can you get out of a non-locking, sort of pen knife-type thingy? As it turns out, not that much.

At least it doesn’t employ ridiculously stiff, slip-lock blade springs while only providing the smallest nail nick to open the dang thing! I guess that’s why 7 out of 10 Czech manicurists who recommend knives recommend the Mikov Kostka.

Handle Dimensions

The handle length of the Kostka is 3”, and the whole knife, fully opened, is just over 5 9/16”. The closed knife height, the same as its body width (you know, the square thing), is a mere 7/16″ thick.

Hardware

There is no fastening hardware to speak of here.

The pivots (the ends of those U-shaped loops that connect to the tang) are spaced with very thin washers, and I see no way, short of prying the loops off the square tang, to disassemble the Kostka. If you did that, reattaching those busted loop pivots may be a lost cause. But what do I know?

FWIW, there’s no specific mount of any kind for a lanyard/fob, not that folks typically attach a fob to these knives anyway. I hope.

Original Packaging

The factory packaging offered by Mikov is a 4-color printed, straight tuck end (STE) folding carton with side hang tabs.

Yeah, sort of like a flattened ointment box. What were you expecting, a Fabergé Egg?

Weight

This little chunk of solid, stainless steel weighs just under 1.4 oz.

It certainly won’t weigh you down, but please be careful. It could very well do serious damage to your washing machine when it’s left forgotten in your jeans pocket and your husband does the laundry. (You guys do laundry, right?)

Knife Karen Nitpicks

I think the Mikov Kostka is a cool, bright and shiny rectangular prism riff on a 131-year-old legendary knife design. But I have more than a few complaints to file with the manager over this one.

- The knife is called Kostka (cube in Czech) but this thing is not a cube! That’s false advertising! Of course, the Mikov Obdélníkový Hranol (rectangular prism in Czech) doesn’t really roll off the tongue, does it?

- Mikov claims that the Kostka is “an original design and opening mechanism”. Incorrect on both counts!

- Mikov also says ladies will appreciate the knife because it won’t stress or damage their fingernails. While I do have delicate Knife Karen hands, this is NOT a selling point for me!

- The knife steel is 440A. I know Mikov is a very old company, but just because they found a long-forgotten cache of 100-year-old junk low-end steel buried in the back of a warehouse doesn’t mean they should’ve used it! Use modern steel!

- The hardness is 55-57 HRc. If that old cache of junk low-end steel had also contained a century-old pierogi, odds are that the crusty, old dumpling would also be between 55-57 HRc. I am not impressed.

- The entire thing is super-duper-polished! It only looks good until you use it, and then it looks like someone wet-coughed onto a mirror. Yuck.

- The opening mechanism is fun at first, but then quickly gets old, especially because it takes so long to open it. But you can make the fun last a bit longer by timing how fast you can open it one-handed. That extends the fun by an extra day.

- And don’t worry about cutting yourself (or anything, for that matter). It’s as dull as ditchwater (yes, I meant ditchwater. Look it up. Dishwater is not truly dull now, is it?).

Price

Seth V of KnifeCenter charged me $39.95 (thanks, Seth!). I bought it because I thought it would be interesting. That it was. That’s all.

Verdict

The Mikov Kostka is a very pretty, bright and shiny, and very old design for a puzzle of a knife. The design has been reborn many times over in the past 131 years. Since being patented in the US in 1893, knives that have used the design have been called:

- Flip Flop Folder

- Tri-Fold

- Easifold

- Funny Folder

- Swing Blade

- 3D Folder (I made up this name myself, because 1. I think it’s fitting for the modern interpretation of this design, and 2. Why not?)

These knives have frequently been released over the years as promotional items because of the low manufacturing cost, and cheap materials, used to make them. There are a few examples of much nicer models using quality steels, but with the Kostka, it’s more flash than dash in terms of being a knife you’d actually want to use.

The one I bought came with a very dull blade, and being made of antique 440A steel with an HRc rating of only 55-57, it’s not a promising candidate for ever getting very sharp. Mikov really should have used a higher-grade steel, even if this knife design has traditionally been made in 440A (the only reason for which is because it’s so bloody old!).

I like the Kostka very much for what it really is: a novelty item, a collector’s piece, and a beautiful example of solid knife-crafting work.

It’s fun to first figure out how to open it, and even more fun to give to an unsuspecting person and tell them this is your knife. They will look at you funny, thinking you’ve lost your mind! That’s always a treat.

The dazzling mirror-finished blade and swiveling loops that make up the body are both a blessing and a curse, as they are genuinely beautiful – until you touch them, which you must do to open it, and then it’s just gross. I refuse to wear little, white cotton gloves everyday just in case I might need to open my EDC.

Overall, I do not believe the Mikov Kostka is a worthy blade for me to carry, despite its nice, small size and safely enveloped blade when closed. To me, it just doesn’t make the cut. ![]()